Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils is the peak representative body for the Muslim community in Australia. Our organisation is comprised of 9 State & Territory Councils with nearly 150-member organisations across the country. While we are a faith-based body our areas of interest are broad ranging and reflect the significant input that members of the Muslim community have to Australian society generally.

The Commonwealth has initiated a review to look at ways for government and the community to work together to support a cohesive multicultural society and advance a vibrant and prosperous future for all Australians. The Australian Government’s decision to initiate a review into multiculturalism comes at a pivotal moment in our nation’s history. In a world that is rapidly evolving and interconnecting, the need to evaluate and reinforce the core tenets of our multicultural fabric has never been more pressing. The recent data from the 2021 Census, which underscores the nation’s growing diversity, serves as a testament to Australia’s position as one of the world’s most cohesive multicultural societies. However, the continuous evolution of our society, with its complexities and challenges, necessitates a thorough assessment. This review is not just a reflection of the government’s commitment to ensure an inclusive society but also an acknowledgment that policies and frameworks must evolve in tandem with changing demographics and societal nuances.

Australia’s multicultural framework has benefited greatly from the Muslim community, which has been an integral part of the country’s fabric for centuries. The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC) submits this document to highlight the contributions, challenges, and recommendations pertinent to the Muslim community within the broader context of multicultural Australia.

Our history begins long before recent waves of migration, with the Macassan traders from Indonesia arriving on the northern shores in the late 1700s. This early connection with Indigenous communities represents one of the first cross-cultural interactions in Australia’s history. Subsequently, the Afghan cameleers, navigating and connecting vast arid stretches of the continent, contributed to key infrastructure that is still acknowledged today, such as the “Ghan” railway line.

In the post-war period, Australia saw an influx of Muslims from diverse backgrounds, including countries like Lebanon, Turkey, and Bosnia. Recent decades have seen arrivals from Afghanistan, Iraq, and other nations. These individuals and families have not just settled here but have actively contributed to the nation’s socio-economic development. Whether in the culinary arts, healthcare, education, or business, the Muslim footprint is significant.

However, the journey hasn’t been without challenges. From integration hurdles to instances of discrimination, the community has faced its share of adversities. It’s essential to recognize these challenges to ensure that multiculturalism remains a tangible and positive experience for all.

This submission has three primary objectives:

- To provide a comprehensive overview of the Muslim community’s historical roots and contributions in Australia.

- To address the contemporary challenges faced by the community.

- To present actionable policy recommendations to enhance multiculturalism and inclusivity.

We believe that an informed understanding of our shared history is crucial for framing our future. Through this submission, AFIC aims to enrich the conversation around multiculturalism, offering insights grounded in the lived experiences of the Muslim community in Australia.

2. Historical Context

2.1 Macassan Traders

The relationship between Australia and its northern neighbours, particularly the Indonesian region, is centuries old, dating back to the late 1700s with the arrival of the Macassan traders. These seafarers, primarily from the Sulawesi region, were drawn to the northern shores of Australia, seeking the trepang (sea cucumber), a delicacy highly prized in Chinese markets. Their voyages were not simple trading missions; they resulted in some of the earliest documented cross-cultural exchanges between the indigenous communities of Northern Australia and foreign visitors.

The interactions between the Macassans and the Aboriginal communities were largely peaceful and mutual. The Macassans set up seasonal camps, processing the trepang before making the return voyage. During their stays, they engaged with the Indigenous inhabitants, leading to shared knowledge, intermarriage, and a blending of customs. This harmonious exchange is evident in various aspects of Indigenous culture today. For instance, some Aboriginal languages of Northern Australia have borrowed words from the Macassan language, and elements of Macassan culture persist in Aboriginal art and stories.

The Macassan connection underscores the fact that Australia’s interaction with the Muslim world is not a recent phenomenon but is deeply rooted in the nation’s early history. The remnants of these interactions, whether in the form of tamarind trees or ancient rock paintings depicting Macassan praus (boats), provide a tangible link to this foundational relationship.

2.2 Afghan Cameleers

The narrative of Australia’s internal exploration and connectivity during the 19th century is incomplete without acknowledging the pivotal role of the Afghan cameleers. These hardy individuals, primarily Muslims from regions that are now parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, were responsible for opening up vast stretches of Australia’s arid interior.

Australia’s mid-late 19th-century ambitions of exploration and establishing overland telegraphic and rail connections presented unique challenges. The nation’s vast deserts and the absence of reliable transportation meant that traditional methods were unsuitable. Enter the cameleers. With their unparalleled knowledge of camel handling and desert navigation, they became indispensable to the era’s major exploration and infrastructure initiatives.

The Afghan cameleers were responsible for transporting goods, mail, and essential supplies between remote settlements. They were integral to significant projects like the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line and the establishment of the Trans-Australian Railway. Their legacy lives on in the famous “Ghan” railway line, named in honour of their contributions.

However, their contributions came with personal sacrifices. Many of these cameleers faced social isolation, living on the fringes of the communities they served. Though their efforts laid the groundwork for the development of inland Australia, they often faced discrimination and were seldom integrated into mainstream society. Nevertheless, their enduring legacy can still be felt in towns like Marree and Farina in South Australia, where mosques and cemeteries stand as testaments to their presence.

2.3. Post-war Migration

The end of World War II marked a turning point in global geopolitics and demographics, with Australia emerging as a focal point for many seeking a fresh start. The nation’s post-war immigration policy aimed to populate the continent, leading to a diverse influx of migrants, including a significant number from Muslim-majority countries.

Communities from Lebanon, Turkey, and Bosnia, among others, began establishing roots in Australia during this period. Unlike the temporary nature of the Macassan interactions or the isolated experiences of the Afghan cameleers, post-war Muslim migrants were coming to build a life and contribute to the growing multicultural mosaic of Australia.

The contributions of these communities were multifaceted. Economically, they filled critical labor shortages, aiding in post-war reconstruction efforts. Culturally, they enriched the Australian way of life, introducing new cuisines, arts, and traditions. Cities like Sydney and Melbourne began to host vibrant Muslim communities, with mosques, schools, and community centres sprouting up to cater to their needs.

However, like many immigrant groups, Muslim migrants faced challenges in their early days. Integration into a predominantly Anglo-Australian society presented cultural and social hurdles. These communities often had to navigate between preserving their cultural identities and adapting to their new homeland’s societal norms. Despite these challenges, the post-war Muslim migrants have undeniably left an indelible mark on the nation’s social fabric.

These historical touchpoints, from the early Macassan traders to the contributions of postwar Muslim migrants, provide a holistic view of the Muslim community’s longstanding relationship with Australia. Each era underscores the community’s adaptability, resilience, and enduring commitment to contributing positively to the nation. Through these narratives, it becomes clear that the Muslim experience is not an appendage to the Australian story but an integral thread that adds depth and diversity to its tapestry.

3. Contributions to Australian Society

3.1 Economic Contributions & the Halal Industry

The economic tapestry of Australia has vibrant threads woven by the Muslim community, embodying the entrepreneurial spirit and the drive to innovate. From bustling marketplaces in Sydney to major industries that serve international markets, the Muslim community’s touch is evident.

For instance, Australia’s halal food industry, led and managed primarily by Muslim entrepreneurs, has unlocked unique, lucrative global markets.

Based on the recent State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2019-20, conducted by the research firm DinarStandard in Dubai, there’s burgeoning potential for Australian food manufacturers within Islamic markets. The research indicates that in 2018, global Muslim expenditure on halal food scaled to US$1.37 trillion (equivalent to AU$2.02 trillion), marking a 5.1% growth compared to the previous year. Projections suggest that this market is on an upward trajectory, with an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.3%, potentially reaching US$1.97 trillion (around AU$2.90 trillion) by 2024.

With a strong global reputation, Australia stands as one of the top contenders in the food and beverage export realm, particularly in sectors like meat and grains. A retrospective glance at the 2014-15 period shows Australian food and beverage exports amassing nearly AU$19.6 billion. An analysis by the Australian Food & Grocery Council from that period estimated that a significant 66% of these exports had halal certification, approximating to AU$13 billion. In 2020 the total export value surged to over AU$23 billion, although this marked a dip from the AU$26 billion peak in 2019, mainly attributed to the pandemic’s impact. Thus, the global halal food and beverage exports from Australia presently stands over AU$17 billion and continues to show promising growth.

In terms of trade partners, Australia’s most substantial halal exports target the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, with countries like Malaysia and Indonesia following closely. In the halal market sphere, Australia currently occupies the fourth rank as the most significant exporter to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries, having exports valued at an impressive AU$7.8 billion in 2018. Based on the projected CAGR of 6.3%, the subsequent decade is poised to witness a twofold increase in exports, potentially hitting AU$14.6 billion.

A closer look at the specifics of these exports to the OIC in 2018 shows meat and live animals leading the charge with an export value of AU$3.1 billion, positioning Australia just behind Brazil. Cereals also held their ground, with exports valued at AU$1.9 billion.

Parallelly, the domestic halal food market in Australia is experiencing significant expansion, currently valued at an annual expenditure of AU$1.7 billion. With the Australian Muslim community, currently hovering around the 850,000 mark (representing 3.2% of the nation’s total population), it’s noteworthy that Islam is now the second-largest religious group in Australia, following the combined Christian denominations. Census data spanning from 2006 to 2021 showcases the steady growth of the Muslim population in Australia, almost doubling from 1.7% to 3.2%. Forecasts suggest that by 2050, the numbers could soar above 1.5 million. It’s worth highlighting, however, that historical data indicates the community’s growth rate often surpasses predictions. Thus, the 1.5 million figure is more plausible by 2040, and by 2050, the community might swell to 2 million, constituting roughly 5.5% of Australia’s total population.

Drawing insights from these numbers, it’s evident that Australia’s halal sector will only grow in prominence, further solidifying its crucial role in the nation’s economic fabric. The sector’s influence is particularly significant in fostering trade relations, especially with Southeast Asian nations, given Australia’s strategic geographical proximity.

In the backdrop of the Australian government’s review into multiculturalism, the halal sector’s burgeoning significance cannot be understated. It stands as a testament to how deeply intertwined Australia’s multicultural fabric is with its economic prosperity. Such sectors highlight the tangible benefits of a diversified, inclusive society, where cultural practices can be seamlessly translated into economic opportunities, fostering mutual growth.

As the government evaluates the existing frameworks and policies to further advance multiculturalism, the halal sector serves as a model of how cultural respect and understanding can lead to mutual economic benefit. Recognising and nurturing such sectors will be paramount not only to upholding our multicultural ethos but also in charting a robust economic future for Australia. Yet, the community’s economic presence isn’t limited to specific niches. Across fields like medicine, engineering, and information technology, Muslim professionals not only serve vital roles but lead and innovate. Their dual identity—both as Australians and as part of the global Ummah—often positions them ideally for international collaborations, expanding Australia’s reach and influence.

3.2 Cultural Contributions

Australia’s cultural landscape, celebrated for its diversity, has been substantially enriched by its Muslim residents. The community’s influence has translated into various facets of cultural life, offering both traditional perspectives and modern interpretations.

Festivals, for instance, have transformed from community-only events to grand citywide celebrations. Eid in Melbourne or Sydney isn’t merely a Muslim affair; it’s an Australian event, a testament to cultural integration. Likewise, the Ramadan night markets, with their melange of cuisines from the Muslim world, have become an anticipated event, drawing diverse crowds.

In the realm of the arts, Muslim voices bring forward unique narratives. Artists like Abdul Abdullah challenge societal perspectives and foster introspection. Moreover, authors such as Randa Abdel-Fattah give depth to the Australian literary scene, weaving tales that resonate across diverse audiences.

3.3 Social Contributions

The heart of any society lies in its social bonds, in the bridges built between communities, and in mutual understanding. The Muslim community in Australia has been a keystone in building and nurturing these bonds.

In the sporting arena, individuals like Bachar Houli have not merely showcased their prowess but have also served as role models, illustrating that an Australian identity can encompass varied backgrounds. Such figures are essential for young Australians, showing them the strength in diversity.

Furthermore, the community’s civic engagement has manifested in numerous ways. Organisations such as the AFIC don’t merely cater to Muslim interests but actively engage in interfaith dialogues, community outreach, and charity efforts. This proactive involvement extends to education too, with Islamic Schools, established originally by AFIC, now present across the nation offering an amalgamation of academic excellence and cultural immersion.

In essence, the Muslim community’s contributions in Australia, be they economic, cultural, or social, don’t stand in isolation. Instead, they intertwine, culminating in a comprehensive narrative that showcases the essence of multicultural Australia—a story of unity in diversity, of shared dreams and aspirations, and of a collective journey towards progress.

Australia’s robust multicultural framework is distinctly reflected in the flourishing contributions sectors like halal make to the nation’s economy. These contributions embody the vision of a society where diverse cultures coexist, collaborate, and create shared value. However, while we celebrate these successes, it’s essential to acknowledge that challenges still linger. The very need for this review underscores the existence of systemic barriers and experiences of discrimination that segments of our multicultural community encounter. While we’ve made significant strides in harnessing the collective strength of our diversity, the path ahead requires us to address these challenges head-on, ensuring that every individual, irrespective of their cultural or religious background, fully participates and prospers in the Australian story.

4. Challenges & Barriers

In the backdrop of Australia’s proud multicultural legacy and the remarkable contributions of diverse communities, it’s pivotal to address the nuanced challenges faced by specific groups to further the goals of inclusivity and cohesion. The Australian Muslim community, with its rich history and significant contributions, unfortunately, confronts a range of barriers that require thoughtful consideration within this review. Highlighting these challenges is not to overshadow the positive experiences and integrative successes of many Muslim Australians. Instead, it’s a commitment to recognising, understanding, and addressing the systemic issues that persist. These challenges, from societal prejudices to economic disparities, shape the lived experiences of many Muslim Australians and serve as a testament to the work that lies ahead in ensuring that the multicultural fabric of Australia is not just celebrated but also actively nurtured.

4.1. Islamophobia and its repercussions

Islamophobia is a specific form of racism. This racism manifests as prejudice, discrimination, and negative stereotypes directed at Islam and Muslims. Rooted in historic misrepresentations and fuelled by global political tensions, Islamophobia represents a structural and pervasive bias that impacts the day-to-day lives of many Muslim Australians.

Contemporary manifestations of Islamophobia range from verbal abuse and hate speech to more overt acts such as physical assaults, mosque vandalisms, and at its extreme, terror attacks against Muslim communities, like the tragic incident in Christchurch, New Zealand. The Australian Human Rights Commission has reported increased incidents of Islamophobia, especially against visibly Muslim women.

The impact of Islamophobia extends beyond individual incidents of prejudice or violence. It affects the psychological well-being of Muslims, engenders mistrust, and inhibits their full participation in social and civic life. There’s evidence to suggest that the experience of racial and religious discrimination can have long-lasting mental health impacts and can lead to feelings of isolation, anxiety, and lower self-esteem.

Islamophobia isn’t just an interpersonal issue, it is structural. Discriminatory policies or practices that target or disproportionately impact Muslims — such as racial profiling, excessive surveillance of Muslim communities, or biased immigration policies — perpetuate an environment of distrust and marginalisation.

Addressing Islamophobia is not just about combating individual prejudices but dismantling a wider framework of racism. Recognising Islamophobia as a form of racism is the first step, followed by proactive measures to educate, sensitise, and create robust institutional mechanisms that counteract its spread and mitigate its repercussions.

4.2. Media portrayal and its influence on public perception

The media plays a pivotal role in shaping public perceptions. Unfortunately, media coverage of Muslim Australians often leans towards the negative, disproportionately highlighting extremist views or actions while neglecting the broader, more representative narratives of the community. A study by non-profit organisation, All Together Now, found that 75% of opinion pieces about Muslims in Australian media had negative connotations perpetuating stereotypes that exacerbate Islamophobia. [1]

The skewed representation fails to capture the rich tapestry of experiences, contributions, and aspirations of Muslim Australians. This media bias not only fuels misconceptions but also reinforces divisive narratives, making integration and mutual respect more challenging to achieve.

In an American Study, Covering Muslims: American Newspapers in Comparative Perspective, which tracked over 250,000 news pieces, found similar results. In fact the authors are quotes as saying:

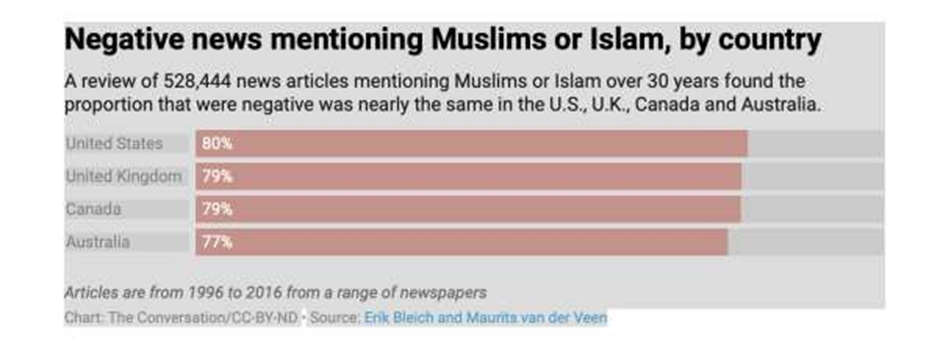

“To better grasp the evolution of media portrayals of Muslims and Islam, our 2022 book, “Covering Muslims: American Newspapers in Comparative Perspective,” tracked the tone of hundreds of thousands of articles over decades. We found overwhelmingly negative coverage, not only in the United States but also in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia.”[2]

And

To find out, we collected 528,444 articles mentioning Muslims or Islam from the same time period from a range of newspapers in the U.K., Canada and Australia. We found that the proportion of negative to positive articles in these countries was almost exactly the same as that in the United States.

In the Australian Human Rights Commission Report – Sharing the Story of Australian Muslims, it noted that one of the key themes raised by Australian Muslims was:

“…a correlation between negative media and political narratives about Muslims and Islam and an increase in aggression and violence towards Australian Muslims. The perpetuation of stereotypes and the inclusion of misinformation about Muslim people and Islam were identified as particularly damaging aspects of these narratives.” [3]

The media’s portrayal of any group holds power not just in shaping individual perceptions, but in directing the broader narrative of a society. In the context of the multicultural framework, a consistent negative depiction of Muslims can inadvertently create divisions, fuelling stereotypes and fostering mistrust within communities. A society thrives when all its members, regardless of their background, feel seen, respected, and understood. However, when mainstream media perpetuates a single, often negative, story about a particular community, it challenges this harmony and threatens social cohesion.

Within Australia’s multicultural framework, the objective is to cultivate an inclusive society where every individual feels they belong and can contribute positively. The media plays a pivotal role in this aspiration. Addressing and rectifying the negative portrayal of Muslims is not just about fairness to the Muslim community; it’s about preserving the unity and shared values of the entire Australian society. Recognizing the role of media in this dynamic is crucial for the Multicultural Framework Review, as it seeks to identify barriers and potential solutions to strengthen Australia’s multicultural identity and social cohesion.

4.3. Economic and employment barriers

Despite their considerable contributions, Muslim Australians often encounter economic and employment barriers. Discrimination during hiring processes, limited recognition of overseas qualifications, and lack of culturally sensitive workplace policies can hinder their career progression. A report from the Australian National University demonstrated that candidates with non-Anglo names, including Muslim names, had to submit more applications to get a call for an interview compared to candidates with Anglo-Saxon names. Such barriers limit the economic potential of Muslim Australians, stifle innovation, and prevent businesses from tapping into the diverse insights and skills this community offers.

In the study, thousands of fictitious resumes were sent in response to job advertisements, with the only difference being the name of the applicant. The intention was to test the level of discrimination faced by job applicants with non-Anglo names. The names represented various ethnic backgrounds, including Chinese, Middle Eastern, Indigenous, and Italian names, to name a few.

The findings were significant:

- Candidates with Chinese names had to submit 68% more applications to get the same number of call-backs as an applicant with an Anglo-Saxon name.

- Those with Middle Eastern names had to submit 64% more applications. • Indigenous names needed 35% more applications, and

- Italian names required 12% more applications.

This clearly demonstrated that racial discrimination was a tangible barrier in the Australian job market. The experiment was controlled for all variables (e.g., education, work experience) except for the name. So, the disparity in call-backs can only be attributed to bias.

Such findings are concerning as they imply a systemic bias in hiring processes, which can lead to long-term economic and social implications. Discrimination at the entry point (job application) limits career opportunities and advancement, potentially leading to lower lifetime earnings and limited contributions to the economy.

This kind of discrimination, especially against names associated with Muslim identities, highlights a clear challenge in ensuring equitable economic opportunities for Muslim Australians. Addressing such biases is not just morally imperative but also economically sensible, as it allows the nation to fully benefit from the skills and talents of its diverse population.

4.4. Assimilation pressures versus the reality of integration

The expectation for immigrants, especially those from non-Western backgrounds, has often leaned towards assimilation – adopting the cultural norms of the majority while sidelining their cultural identities. However, assimilation can result in the loss of rich cultural traditions and values that migrants bring with them. Australia’s strength lies in integration – where everyone, irrespective of their background, has an equal stake in society and can retain their unique identities while contributing to the national fabric. Integration fosters mutual respect and understanding, enriching Australia both culturally and socially. Yet, there exists a gap between the ideal of integration and the pressures many Muslim Australians feel to assimilate. Bridging this gap requires proactive efforts from all sections of society, including policy frameworks that support and encourage genuine integration.

The discourse surrounding immigrants and their integration into Australian society is multifaceted. Historically, the idea of assimilation was predominant, where immigrants, especially those from non-Western nations, were tacitly encouraged to adopt Australian cultural norms, often at the expense of their own heritage. This approach, while facilitating superficial societal cohesion, risks erasing the diverse mosaic of cultural traditions and values immigrants bring, impoverishing Australia’s cultural tapestry in the process.

The shift towards a philosophy of integration over the past decades recognises the importance of maintaining individual cultural identities within the broader framework of national identity. Integration, as opposed to assimilation, champions the idea that it’s not only possible but beneficial for immigrants to be both proudly Australian and proudly connected to their cultural roots. Such a perspective does more than just respect individual identities; it brings forth a multitude of perspectives, fostering innovation, creativity, and richer community interactions.

However, the lived experiences of many Muslim Australians indicate that the societal push towards assimilation is still palpable, even if unintentional. The subtle pressures to conform can range from workplace expectations to societal prejudices against overt displays of cultural or religious identity. These pressures can sometimes translate into feelings of alienation or the perception that one has to choose between being “Australian” and being true to one’s heritage.

A poignant aspect of this struggle revolves around family traditions and Islamic family practices, which, although integral to many Muslim Australians’ lives, find little acknowledgment in the nation’s legal structures. The absence of formal recognition for Islamic family traditions in law, or policy, has inadvertently pushed some within the community to seek unofficial agreements to preserve their traditions. This alternative, while providing a semblance of cultural continuity, has its pitfalls. With the lack of official oversight, there’s potential for exploitation, particularly of the vulnerable, thus widening the chasm between policy and lived experience.

Furthermore, while Australia proudly projects itself as a pluralistic society, this pluralism sometimes feels more aspirational than actual, especially when one observes the gaps in policy and legal recognition of diverse cultural practices. Achieving true pluralism demands both systemic and grassroots transformations. Policies must not only tolerate but celebrate diversity, ensuring inclusivity in public institutions, educational curriculums, and workplaces. Furthermore, the recognition and integration of diverse family traditions and practices into the legal system would not only acknowledge the rich tapestry of Australian society but also provide protective frameworks to prevent potential exploitation.

To achieve the vision of an integrated society, Australia needs to move beyond mere acceptance of diversity towards a deeper understanding and appreciation of it. This involves both top-down and grassroots efforts. From a policy perspective, there’s a need for frameworks that not only tolerate but celebrate diversity, ensuring that public institutions, educational systems, and workplaces are inclusive and culturally sensitive. On a community level, initiatives that foster intercultural dialogue, collaborative projects, and shared spaces can help bridge cultural divides, encouraging a society where every individual, irrespective of background, feels seen, valued, and integral to the nation’s story.

4.5. Social Cohesion in Australia

In understanding the complexities these challenges pose for the Muslim community, it is instructive to consider the broader context of public sentiment toward immigration and multiculturalism. The findings of the Scanlon Foundation’s 2022 report on social cohesion provide an important perspective on this.[1] While the report underscores a growing and predominant acceptance of multiculturalism in Australia, with significant increases in positive

attitudes toward ethnic diversity over recent years, there remains evidence of significant issues in relation to discrimination and racism.

The report notes that approximately one in every six Australians had experienced some form of discrimination due to their skin colour, ethnic origins, or religious beliefs — a statistic that remains largely unchanged from the previous years. Delving deeper, the lens of discrimination focuses more sharply on immigrants and those speaking languages other than English, with nearly a quarter of the former and over a third of the latter reporting discriminatory experiences. Reflecting on the past, we observe an alarming surge in discrimination, which climbed from a modest 9% in 2007 to a staggering 20% just a decade later. And while recent years have seen a slight abatement, these numbers still hover above the levels seen a decade ago.

A key data point in the Scanlon Report was that 29% of Australians held negative views of Muslims. While this is well down on the 40% in the previous report it still indicates that nearly a third of all Australians hold views that are negative about Muslims. This suggests that despite our progress, the journey to full acceptance and understanding has a long way to go yet. In addressing these challenges and barriers, it is crucial to ensure that the policies and frameworks set forth in this review genuinely resonate with the lived experiences of Muslim Australians. Only then can Australia continue its journey towards being a truly inclusive and harmonious multicultural society.

5. Effectiveness of Multiculturalism in Australia

Australia, often hailed as a multicultural success story, has embraced a diverse tapestry of cultures, religions, and ethnicities. This ethos of multiculturalism, deeply entrenched in our national identity, isn’t just a nod to diversity but a testament to our belief in the strength of unity in diversity. Let’s delve deeper into understanding how multiculturalism has fared, particularly focusing on the Muslim community and others, while identifying areas for introspection and improvement.

Multiculturalism has undeniably offered significant benefits. The policies, initially instituted in the 1970s, were transformative, challenging a monolithic perspective and creating a pluralistic society. For the Muslim community, these policies have facilitated the establishment of mosques, community centres, and halal outlets, allowing for the free practice of faith and traditions. Moreover, the multicultural framework has opened doors for

the rise of notable Muslim personalities in fields as diverse as politics, sports, and entertainment. It’s not just the Muslim community; many other immigrant groups have found a voice, representation, and acceptance in the Australian fabric.

However, while the overarching framework has been promising, there have been areas where multiculturalism seems to be more symbolic than substantive. Economic disparities persist. Many Muslims and other ethnic minorities find themselves disproportionately represented in lower-paying jobs, despite having commendable educational backgrounds and professional experiences. This can be attributed to a mix of systemic issues and latent biases.

Moreover, representation in powerful and influential roles, both in the public and private sectors, leaves much to be desired. The mosaic of multicultural Australia isn’t always accurately mirrored in our boardrooms or parliamentary benches.

The interplay between federal and state policies adds another layer of complexity. While the federal government sets the tone with overarching policies, individual states have the autonomy to interpret and implement them as they deem fit. This has led to both harmonies in some areas and disconnect in others. For instance, while New South Wales and Victoria might have robust community engagement programs, the nuances of their initiatives vary, catering to their demography. These policy variations can sometimes lead to gaps or overlaps in service provision and community engagement.

Arguably, one of the most potent tools in shaping perceptions and fostering integration is education. Our schools and universities have a pivotal role in the multicultural narrative. The incorporation of diverse histories, perspectives, and stories in the curriculum has been a commendable step. However, it’s not just about what’s taught but how it’s taught. The pedagogy needs to be inclusive, promoting critical thinking and challenging stereotypes. Outside the classroom, fostering environments where multicultural events, exchange programs, and interactions are encouraged is equally crucial. These formative years can shape perceptions and attitudes that last a lifetime.

Then there’s the role of the media, an entity with the power to build bridges or erect walls. The Australian media landscape, on one hand, has showcased heartwarming stories of multicultural success, celebrating festivals like Eid or Diwali with the same fervour as Christmas. On the other hand, there have been instances where the media has been found wanting in its representation. Sensationalism, especially around topics concerning Muslims or issues like immigration, has sometimes overshadowed nuanced, balanced reporting. This not only perpetuates stereotypes but can also inadvertently fan the flames of division. In conclusion, the Australian multicultural experiment has been, by and large, a success story. It’s a testament to our nation’s resilience, openness, and forward-thinking. However, like all great narratives, there are areas of improvement. The journey towards perfecting our multicultural society is ongoing. It requires constant reflection, dialogue, and the collective will of all stakeholders involved. As we chart the course for the future in this multicultural framework review, it’s vital to remember that our strength doesn’t just lie in celebrating our differences but in ensuring that every voice, irrespective of its cultural or religious timbre, resonates with equality, dignity, and respect.

6. Enhancing the Multicultural Framework: Policy Recommendations

Over the decades, our national fabric has been woven with the threads of diverse communities, each adding their unique colours. However, as we look ahead, there are areas where this fabric shows signs of wear, and new patterns need to be woven in to reinforce its strength. Below are some crucial recommendations for a more inclusive tomorrow.

6.1. The Power of Education

Imagine classrooms where young minds aren’t just taught about the world wars or the

Australian gold rush but also delve deep into the tales of the Silk Road or the poetic verses of Rumi. Expanding our curriculum to be more inclusive is a powerful step forward. But it doesn’t stop there. What if students from Melbourne could experience the rhythms of life in Darwin? National exchange programs could allow this cross-cultural exposure. And at the heart of these educational endeavours are our teachers. By equipping our educators with tools to foster inclusivity, we’re laying the foundation for a generation that thrives on understanding.

Recommendations

- Curriculum Expansion – Incorporate a more inclusive curriculum that integrates the histories, achievements, and cultural nuances of diverse communities, especially underrepresented ones like the Muslim community.

- Multicultural Exposure Programs – Introduce exchange programs within the country that allow students from various backgrounds to spend time in different parts of Australia, experiencing firsthand its rich multicultural tapestry.

- Teacher Training – Equip educators with the tools and training to address biases, promote critical thinking, and foster an environment of inclusivity and respect.

6.2. Legal Safeguards

Every individual deserves to feel protected. Strengthening our anti-discrimination laws ensures that biases don’t dictate opportunities. Imagine a skilled doctor from Cairo or an engineer from Islamabad, their potential is untapped because their qualifications aren’t recognised. A streamlined recognition process can change that narrative. And when misunderstandings arise, specialised mediation panels could be the spaces where they’re resolved, ensuring that every voice is heard.

Recommendations

- Strengthening Anti-discrimination Laws – Revise and update existing antidiscrimination laws to better address modern challenges, with more significant consequences for businesses and individuals found guilty and to ensure a nationally consistent framework.

- Recognition of Foreign Qualifications – Establish a streamlined process for the recognition of overseas qualifications, ensuring that immigrants, including Muslims, are not unduly disadvantaged in the job market. This should include clearer information provided to skilled migrants and the strengthening of the recognition of professional experience, even if obtained overseas, as part of the qualification recognition process.

- Recognition of Religious practices – The incorporation of provisions within Australia’s existing legal frameworks to recognise and respect religious practices, particularly in the areas of family law and inheritance law.

- Specialised Mediation Panels: Create panels to address grievances related to cultural or religious discrimination, ensuring that victims have a voice and that disputes are resolved amicably.

6.3. Voices in Public Sectors

Our public offices should be a mirror, reflecting the diversity of our nation. While merit should always be the guiding light, diversity quotas can help illuminate paths for the underrepresented. Through targeted leadership programs and nurturing mentorship initiatives, we can ensure that the public sector becomes a mosaic of Australia’s multiculturalism.

Recommendations

- Diversity Quotas – While meritorious appointments should be the norm, consider introducing diversity quotas for underrepresented communities in select public roles, ensuring more comprehensive representation.

- Leadership Programs – Initiate leadership programs targeted at minorities, helping them navigate and ascend the ranks within public sectors.

- Mentorship Initiatives – Establish mentorship programs where experienced professionals guide and nurture young talents from diverse backgrounds, promoting understanding and collaboration.

6.4. Media: The Double-edged Sword

Media shapes perceptions, and sometimes, these perceptions can be skewed. Through media literacy programs, we can foster an audience adept at discerning fact from bias. And to the media houses that champion balanced reporting, incentives could be the wind beneath their wings. However, for times when the scales tip, an empowered media oversight body can ensure they’re balanced again.

Recommendations

- Media Literacy Programs – Foster a discerning audience through media literacy programs that teach consumers to critically evaluate content, discerning bias from objective reporting.

- Training of community organisations and leaders in media to build capacity of minority communities to better engage and advocate with all media platforms.

- Incentivise Inclusive Reporting – Provide incentives, like grants or awards, to media houses that actively work towards balanced, nuanced, and inclusive reporting.

- Media Oversight Body – Strengthen the existing media oversight bodies, and simplify the processes, to ensure fair representation of minority groups, addressing grievances, and holding media houses accountable.

6.5. Strengthening Community Bonds

Central to the fabric of our multicultural society are our deeply-rooted communities. In the midst of diversity, local community centres, where interfaith and intercommunity dialogues flourish, serve as vital bridges for mutual understanding. Beyond mere events, culturally funded festivals can transform into powerful platforms of unity, drawing residents together in shared celebration.

However, it’s imperative to recognize that these bonds need to be actively established, nurtured, and fortified. Such social capital becomes invaluable during periods of stress and crises. As the recent pandemic has shown, trust within and around communities plays a pivotal role during challenges. The Covid-19 response stands testament to this – local, placebased communities demonstrated more effective outreach and support compared to larger organizations or even some governmental entities.

Thus, as we shape the nation’s policies, platforms that solicit and incorporate community feedback are essential. This ensures a holistic approach where every individual, from every corner of Australia, has a say in the nation’s direction. Only with such robust community engagement can we be truly prepared for future challenges, ensuring no one is left behind.

Recommendations

- Establishing and Nurturing Community Bonds o Proactively engage with and support community centres, places of worship, and local councils to initiate and sustain interfaith and intercommunity dialogues. o Recognise and emphasise the role of these bonds as crucial social capital, particularly during challenging times, and provide the necessary resources and platforms to strengthen them.

- Resilient Cultural Celebrations o Enhance financial and logistical support for cultural festivals and centres. Go beyond just celebrating Australia’s rich diversity and ensure they serve as platforms for education, interaction, and mutual understanding.

- Use lessons from the Covid-19 response to identify best practices for community outreach during these events and ensure that local communities are at the forefront of organisation and participation.

- Community-Centric Policy Development o Design and promote platforms where members of diverse communities can actively provide feedback on policies, suggest improvements, and raise concerns.

- Prioritise community insights in policy-making, ensuring that every policy is adaptable and resonant with the real-world experiences of Australians from all backgrounds.

- Trust-building Initiatives o Learn from the pandemic’s challenges and successes to develop strategies that bolster trust within communities. This could involve transparency

- campaigns, community trust-building workshops, or collaborations between local communities and larger organizations/government entities. o Encourage larger organisations and governmental bodies to collaborate more closely with local communities, ensuring that the grassroots level is always involved in decision-making processes, especially during crises.

As Australia continues its journey as a multicultural nation, it’s vital that these recommendations are seen not just as prescriptive measures but as evolving guidelines, constantly adapting to the dynamic nature of our society. By fostering understanding, ensuring protection, enhancing representation, and promoting fair media portrayals, we can move towards a more harmonious future where every Australian, regardless of their cultural or religious background, feels truly valued and integrated.

7. Conclusion

Australia stands at a unique crossroads, where its storied past and diverse present offer an unparalleled opportunity to craft an inclusive future. The essence of our multicultural spirit is not just in celebrating our differences but in recognizing that these differences collectively form the mosaic of our national identity.

The journey so far has been commendable. From the waves of immigration that have enriched our shores to the multicultural policies in place, we have strived for an inclusive society. Yet, as highlighted in our discussions, challenges persist. Islamophobia, biases in media portrayal, gaps in the full integration of Muslim Australians, and the tussle between assimilation and genuine integration are real concerns. These are not just issues for individual communities; they’re pivotal for the health of our broader Australian social fabric.

Our recommendations for educational reform, stronger legal safeguards, improved representation, media accountability, and robust community engagement are not just policy shifts. They are investments in an Australia where every voice matters, every culture is celebrated, and every individual, irrespective of their background, feels at home.

In conclusion, the bedrock of our multicultural framework—admired by many nations—is the trust we instil within it and our commitment to nation-building. Its ultimate strength is gauged not just by its existence but by its adaptability and proactive response to challenges. In valuing and reinforcing this trust, we don’t merely preserve Australia’s multicultural essence; we magnify it for the generations that follow. This submission is more than just a call to action; it’s an invitation to unite and craft a legacy of trust and unity—a vibrant tapestry that future Australians will regard with deep pride and reverence.

Yours faithfully

Dr Rateb Jneid President

[1] https://scanloninstitute.org.au/sites/default/files/2022–11/MSC%202022_Report.pdf p.11

[3] https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/ahrc_sharing_stories_australian_musli ms_2021.pdf 4 https://openresearch–

repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/34947/6/03_Booth_Does_Ethnic_Discrimination_2011.pdf

[2] https://theconversation.com/yes–muslims–are–portrayed–negatively–in–american–media–2–political–scientistsreviewed–over–250–000–articles–to–find–conclusive–evidence–183327

[1] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-11/australian-mainstream-media-often-perpetuate-racism-reportfinds/12849912

Multicultural-Framework-Review-Sept-2023-Submission