Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils is the peak representative body for the Muslim community in Australia. Our organisation is comprised of 9 State & Territory Councils with nearly 150-member organisations across the country. While we are a faith-based body our areas of interest are broad ranging and reflect the significant input that members of the Muslim community have to Australian society generally.

In June 2023 the Commonwealth Attorney General tabled before Parliament a proposed Bill titled “Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Prohibited Hate Symbols and Other Measures) Bill 2023”. In the accompanying media release, the Attorney General’s Office stated:

“The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Prohibited Hate Symbols and Other Measures) Bill 2023makes it a criminal offence to publicly display Nazi and Islamic State symbols or trade in items bearing these symbols.

These symbols – the Nazi Hakenkreuz (or hooked cross), the Nazi double sig rune (or ‘SS’ bolts) and the Islamic State flag – are widely recognised as symbols of hatred, violence and racism which are incompatible with Australia’s multicultural and democratic society.

There is no place in Australia for symbols that glorify the horrors of the Holocaust or human rights atrocities.

This ban will not apply to the display and use of the sacred swastika which is of spiritual significance to religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.”1

This move followed a marked and alarming rise in the public display of Nazi symbology in Australia in the preceding 12-24mths with the rise of far-right presence in public protests and other anti-government actions.

AFIC supports the overarching principle of banning symbols of hate that are clear and unequivocal and used for no purpose other than promoting such ideology.

We note, however, that in the public discourse prior to the introduction of this Bill reference was made specifically to Nazi symbology and no mention had been made by the government in relation to the ISIS flag. Despite the rise of ISIS over the preceding decade, and all of the atrocities connected with this group, no government had moved to ban its imagery. This is, we submit, partly due to the fact that the imagery used on the ISIS flag is a usurpation of mainstream Islamic concepts used by over 1.8B Muslims globally every day. A former NSW police officer Kristy Milligan writes:

‘While many other symbols used by extremist groups aren’t as clear-cut, there’s no ambiguity about the meaning and intent behind symbols such as the Hakenkreuz [Nazi swastika] or Totenkopf [Nazi skull symbol],’ Milligan says. ‘Specifically, the criminalisation of unambiguous Nazi symbols in Australia would equip frontline officers with powers to seize materials or detain individuals who publicly display those symbols of hate.’2

Milligan succinctly sums up the fundamental problem with the proposed Bill. The Government has included symbols which over time have become synonymous with hate and a repugnant ideology, Nazism, with others that form a fundamental part of the daily worship of over 25% of the global population which have been usurped by an extremist group.

With respect to the Nazi symbology, we also note the specific reference by the Government that this does not extend to the symbols, very similar in appearance, that are used in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism – yet there is no similar reference to the Islam and Muslims. We do not suggest that a similar reference would in fact address our concerns with the Bill, it would not, but its absence suggests that the Government has failed to properly consult with the Muslim community and indicates a lack of understanding of the implications of its proposed Bill.

We explore these issues in further detail in the balance of this submission but at the outset AFIC wishes to state its opposition for the inclusion of the ISIS Flag in the proposed Bill.

2. Key Aspects of the Bill

The Explanatory Memorandum of the Bill notes:

“1. The Bill would make critical changes to current legal settings to ensure law enforcement can appropriately manage this risk and protect the community from those planning, preparing and inspiring others to do harm by amending the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Criminal Code) to:

- Establish new criminal offences for the public display of prohibited Nazi and Islamic State symbols; and trading in goods that bear a prohibited Nazi or Islamic State symbol (Schedule 1).

- Establish new criminal offences for using a carriage service for violent extremist material; and possessing or controlling violent extremist material obtained or accessed using a carriage service (Schedule 2).

- Expand the offence of advocating terrorism in section 80.2C of the Criminal Code to include instructing on the doing of a terrorist act and praising the doing of a terrorist act in specified circumstances; and increase the maximum penalty for the advocating terrorism offence from 5 to 7 years imprisonment (Schedule 3).

- Remove the sunsetting requirement for instruments which list terrorist organisations and bolster safeguards (Schedule 4).”3

This submission addresses Schedules 1 & 2 only of the proposed Bill. While AFIC has some minor concerns with Schedules 3 & 4 they are not such that we oppose those proposals in principle and as such remain silent on those matters.

We note the following additional matters that are part of the proposed Bill and require further elaboration:

A. The Islamic State Flag is not defined within the Bill. The Explanatory Memorandum notes:

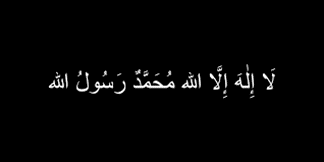

21. The Islamic State flag is a rectangular, black emblem with white Arabic writing, and below the white Arabic writing is a white circle containing black Arabic writing. The white writing is an Islamic creed declaring ‘There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger’. The black writing translates to three words: ‘God, messenger, Muhammad’.

22. It is not intended that the symbol must be displayed on a flag in order to be captured by paragraph 80.2E(a). The word ‘flag’ has simply been used as part of the name of the symbol.”4

The effect of the above, we would submit, is that it is the Arabic text that will in fact be prohibited. Paragraph 22 above makes it clear that the ‘symbol’ being referred to is not the physical flag as such but what is on it i.e., the Arabic text. We oppose this completely.

B. The proposed Bill also includes things which are likely to be confused with, or mistaken for, a prohibited symbol. The Explanatory Memorandum notes:

31. New paragraph 80.2E(d) would have the effect that any symbol that so nearly resembles the Islamic State flag…that it is likely to be confused with, or mistaken for one of these symbols, is taken to be a prohibited symbol. This could include any figure, drawing, symbol, pattern or design substantially similar to the Islamic State…and capable of being reasonably recognised as derived from, or a modified version of, one of those symbols….

And

32. Paragraph 80.2E(d) is intended to recognise that there may be some variations in the ways in which the Islamic State flag…[is]depicted. The legislation is not intended to be so prescriptive in defining these symbols as to exclude these variations from being captured by the provisions, where they would be recognised by the public as being the Islamic State flag…”5

Given that proposed s.80.2E(a) makes it clear that the symbol is not the actual flag itself but what is represented on the flag, i.e., the writing, the implications of s.80.2E(d) are extraordinary. It in effect will mean that any representation of the Islamic testament of faith, the ‘Shahada’ or the Seal of the Prophet (pbuh) is potentially prohibited. The Government may argue that there is an exemption for religious purposes within the proposed regime to deal with this situation, but we respectfully submit that this is woefully inadequate, and we will address this in subsequent sections of this submission.

C. The Bill proposes to use the legal principal of the “reasonable person test” in considering the issue of whether the display of a symbol would disseminate racial hatred or superiority etc. The Explanatory Memorandum notes:

“70. The reasonable person test means that it would not be necessary for the prosecution to prove that the public display of the prohibited symbol actually involved the dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or racial hatred and actually could incite another person or a group of persons to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate others on the basis of race. The fact that it would be reasonable to conclude that the public display of the prohibited symbol has this effect would be sufficient. This recognises that one of the purposes of the offence is to prevent harms of this kind. It also signals that these harms are likely outcomes of the public display of prohibited symbols due to the ideologies they are widely recognised as representing.”

And:

72. …These circumstances are that a reasonable person would consider that the public display of the prohibited symbol involves advocacy of hatred of a group of persons distinguished by race, religion or nationality (a targeted group), or a member of a targeted group (paragraph 80.2H(4)(a)); and involves advocacy that constitutes incitement of another person or group of persons to offend, insult, humiliate, intimidate or use force against the targeted group or a member thereof (paragraph 80.2H(4)(b)).

73. The reasonable person test means that it would not be necessary for the prosecution to prove that the public display of the prohibited symbol actually involved the advocacy of hatred of a group distinguished by race, religion or nationality, and advocacy that constituted incitement of another person or group to offend, insult, humiliate, intimidate or use force or violence against a targeted group or member thereof.” 6

While in most cases the use of the reasonable person test is appropriate the import of that approach in this situation is that it is highly likely, for reasons we shall delve into later in this submission, that the mere presence of something similar to the writing on the Islamic State flag will be deemed to trigger the test in the proposed legislation. At a practical level it would significantly shift the burden and onus of proof from the prosecution to the defendant in these matters. This is not a scenario that we could support in the circumstances.

3. Substantive Submissions – Schedule 1

3.1 What Constitutes a Prohibited Symbol

As mentioned above, the Bill provides no definition of what constitutes a prohibited symbol beyond the wording of s.80.2E itself. This provision simply states:

“80.2E Meaning of prohibited symbol.

Each of the following is a prohibited symbol:

• the Islamic State flag.

• the Nazi Hakenkreuz.

• the Nazi double-sig rune.

• something that so nearly resembles a thing to which paragraph (a), (b) or (c) applies that it is likely to be confused with, or mistaken for, that thing.”

Given that the Islamic State flag is just two items of Arabic writing on a black background the significant and real concern with the interplay between sub-section (a) and (d) above would be that the Arabic writing itself becomes the prohibited symbol. This is clear from the wording of the explanatory memorandum itself.

The question this gives rise to is, why would this be problematic? The answer lies in what the Arabic writing actually is.

The first piece of text, which runs horizontally across the top of the flag is what is referred to as the ‘Shahada’. This is the Islamic testament of faith and represents one of the foundational tenets of the religion that is required to be recited by Muslims multiple times each day.

The images below represent just a sample of the representation of the Shahada and while it can be shown in many different ways, and in different colours, the black and white combination is the most common format that it is done in. This is because the Prophet (PBUH) used a black flag with the Shahada on it as his banner during battles and is in fact the very reason why Islamic State co-opted this imagery for their purposes.

|  |

While there is one predominant form of the Islamic State flag a cursory online search demonstrates that they have used different styles and fonts including the one below.

The font is not very dissimilar to the middle image on the previous page and if one were to remove the background of both images the actual text of the Shahada would be almost indistinguishable from the second and third image above.

This brings us to the second image that has been co-opted by Islamic State, what is known as the Seal of the Prophet – this Arabic text that is positioned below the Shehade. This is not a random phrase or something that Islamic State has created. The words, the font and the format are a replica of the actual Seal of the Prophet (PBUH). This came about during the time of the Prophet when he began to communicate with other leaders and to issue decrees or enter into treaties. He had created a seal that bore the words – Mohammad, Messenger of Allah. His status as a Prophet and Messenger of God was the highest of honors and positions a human could have and was considered the worthiest of being his imprimatur. He never signed any document with his own name but always with the Seal that testified to his status as the Messenger of Allah. There are still relics surviving to this day that show this representation.

|  |  |

We can see from the above images that the representation on the Islamic Flag is an exact replica of these and in fact the most common font used by Islamic State for the Shehade is a copy of the style of writing that is represented on the Seal of the Prophet.

All of the above would, on the face of it, be captured by the wording of s.80.2E as being things that are likely to be confused with, or taken for, the imagery on the Islamic flag and would therefore constitute prohibited symbols unless one of the defenses or exceptions in the latter provisions would apply.

This is an unacceptable position for the Muslim community in Australia to agree to and AFIC rejects this approach in its entirety.

3.2 The Public Display of Prohibited Symbols

To be an offence under the proposed legislation there needs to be a public display of the prohibited symbol which meets certain criteria. The proposed definition of display is:

“80.2F Meaning of displayed in a public place.

(1) A thing is displayed in a public place if it is capable of being seen by a member of the public who is in a public place (whether or not the thing is actually so seen by a member of the public).”

The balance of that section then expands this to ensure that documentation, online and recorded images are included in this definition. The Explanatory Memorandum notes that ‘Public Display’ is meant to carry its normal and usual meaning.

Section 80.2H then proceeds to outline the criteria that must be met by the public display for it to be captured by the law. The relevant sub-sections state:

“(1) A person commits an offence if:

a. the person causes a thing to be displayed in a public place; and

b. the thing is a prohibited symbol; and

c. subsection (3), (4) or (7) applies; and

d. subsection (9) does not apply.…

(3) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), this subsection applies if a reasonable person would consider that the conduct mentioned in paragraph (1)(a):

a. involves dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or racial hatred; or

b. could incite another person or a group of persons to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate:

b. a person (the targeted person) because of the race of the targeted person; or

c. the members of a group of persons (the targeted group) because of the race of some or all of the members of the targeted group.(4) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), this subsection applies if a reasonable person would consider that the conduct mentioned in paragraph (1)(a) involves advocacy that:

a. is advocacy of hatred of:

(i) a group of persons distinguished by race, religion or nationality (a targeted group); or

(ii) a member of a targeted group; and

b. constitutes incitement of another person or group of persons to offend, insult, humiliate, intimidate or use force or violence against:

(i) the targeted group; or

(ii) a member of the targeted group.…

(7) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), this subsection applies if the conduct mentioned in paragraph (1)(a) is likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person who is:

a. a reasonable person; and

b. a member of a group of persons distinguished by race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion or national or social origin; because of the reasonable person’s membership of that group.”

It is not hard to imagine numerous scenarios where a member of the public or an enforcement official could very easily make out a case that would meet one of the above criteria where an individual is doing nothing other than what many Muslims would do in their day-to-day lives.

The imagery discussed in the previous section are not things that exist only within the home or even inside Mosques. They are used and displayed by Muslims every day in a multitude of situations. It is common to see Muslims wear merchandise like that shown below or to have stickers on their cars with either, or both of, the Shahada and the seal of the Prophet.

All of the above, or any variation of them, particularly when represented in the black and white motif could easily be seen by an ordinary person in the street as being Islamic State imagery given the saturation in mainstream media of that imagery and its association with Islamic State. The proposed legislation is very clear in that the intention of the individual displaying this imagery is irrelevant – the only question is whether or not a reasonable person would see it as something that met one of the criteria outlined in the legislation. That criteria in summary are:

- Does it represent racial superiority or racial hatred; or

- Could it incite another person to offend, humiliate or insult a target group; or

- Could it incite the advocacy of hatred; or

- Could it incite another person to insult, humiliate, intimidate or use force or violence.

So, the individual themselves does not need to represent those things, it is enough if the

imagery displayed ‘could’ incite another individual to do any of the above.

A ‘reasonable person’ could very easily argue that those images, because of their public association with Islamic State, could very easily incite an individual who, themselves are not displaying them, towards hatred etc of a targeted group.

In effect the outcome of this proposed legislation would be to assign these images, which are central and foundational to all Muslims, to being the sole right of Islamic State and to be associated with their ideology and nothing else – exactly what Islamic State would want.

It is for these, and the other reasons outlined in this submission, that AFIC opposes the proposed inclusion of this imagery in the Bill.

3.3 Proposed Defences or Exemptions

Sub-sections (9) and (10) outline exemptions and defenses to the provisions. The defenses all relate to the conduct of enforcement officials, those assisting enforcement officials and the conduct of hearings or tribunals – none of which are relevant for these purposes.

The only relevant provision in our submission is:

“(9) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(d), this subsection applies if a reasonable person would consider that:

(a) the conduct mentioned in paragraph (1)(a) is engaged in for a purpose that is:

(i) a religious, academic, educational, artistic, literary or scientific purpose; and

(ii) not contrary to the public interest;”

For the purposes of our consideration in this submission the relevant exemption is in relation to engaging in the alleged conduct for a religious purpose. However, this has limited application in the scenarios we have outlined above. There is no actual religious ceremony or ritual that requires the displaying of this imagery in Islam – this is not how the religious observance takes place for Muslims. So, while there may be versions of this imagery in some shape or form inside a Mosque or Islamic center it is not strictly speaking a religious requirement.

However, this ignores a basic element of the religion i.e., that Muslims look for opportunities to demonstrate and strengthen their connection with Allah(swt) (God) and His Messenger (PBUH). This often includes the wearing of clothing, insignia, ornaments and the displaying of other material that reminds them of this connection. As we have outlined above, the imagery subject of these provisions falls squarely into this category and if this Bill is passed in its current form many Muslims may very well find themselves unable to express their commitment to their faith in ways that have been done for centuries previously.

For these reasons AFIC submits that the exemptions and defenses in the proposed Bill are manifestly inadequate to safeguard the rights of Muslims to express their faith as all other Australians would have the right to do.

3.4 Human Rights Implications

We note that the Explanatory Memorandum makes the following comments in respect to the Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion:

37. Islamic State symbols represent a dangerous ideology that is framed around an extremist and offensive interpretation of Islamic religious doctrine and has been used to justify the commission of terrorist acts and other atrocities. The Islamic State ideology promotes persecution of other faith communities.

38. In criminalising the public display and trade of prohibited Nazi and Islamic State symbols, the offences would protect the rights afforded by Article 18 by preventing these symbols from being disseminated in circumstances that would infringe upon the rights of Australians to worship, observe, practice and teach religion free from harassment, vilification and risks to personal safety.

39. The combined effect of new paragraphs 80.2H(1)(d) and 80.2H(9)(a) would be that, in order for the public display offence to be established, the prosecution must prove that a reasonable person would consider that the person did not publicly display a prohibited symbol for a religious purpose and in the public interest…These requirements are intended to send a strong message to religious groups, courts and the public that the genuine use of an otherwise prohibited symbol by a religious group for religious reasons is not intended to be captured by the offences. A religious purpose would include, for example, the public display of the sacred Swastika in connection with the Buddhist, Hindu and Jain religions. The sacred Swastika is an ancient symbol of peace and good fortune that holds special significance in these faith communities. The symbol was misappropriated by the Nazi regime, and the distinction between the sacred Swastika and the Nazi Hakenkreuz is one which the Bill seeks to make explicit. It is not intended that the ban on the public display or trading of the Nazi Hakenkreuz is to limit the use of the sacred Swastika in connection with religious observance. Accordingly, these measures promote the rights in Article 18 of the ICCPR.”7

With all due respect to the author(s) of the Explanatory Memorandum this passage shows a basic misunderstanding and lack of appreciation of the Islamic faith, how it is practiced in the daily lives of Muslims and the importance of certain symbols and artefacts to Muslims. In this regard we make the following points:

- The use of the phraseology, “Islamic State symbols” in the above passage, and throughout the document is problematic and at the heart of the disconnect we are pointing out. The symbols and images being considered here are NOT Islamic State symbols – they are symbols of Islam and are used and referred to by Muslims globally on a daily basis.

The failure to acknowledge and understand this fundamental point serves to underplay the potential impact the proposed Bill will have on Muslims generally. The more correct terminology would be “Islamic Symbols co-opted or usurped by Islamic State”. At the very least this recognises the central role these symbols play in the faith generally. - The undercurrent throughout the document and the Bill that we are concerned about is aptly demonstrated in the very opening of paragraph 37 of the Explanatory Memorandum noted above which says, “Islamic State symbols represent a dangerous ideology…” We take particular objection to this phraseology. Firstly, they are not “Islamic State” symbols, as we point out above, but even more importantly the symbols themselves do NOT represent a dangerous ideology – they represent Islam itself. We find this language to be deeply offensive and hurtful.

The fact that the drafters of the document themselves see these symbols in this way simply highlights the problems we have alluded to that will arise if the Bill is passed. The unfortunate and simple truth is that law enforcement, security organisations and political leaders start from a position where they now see these symbols as being at the heart of the problem. Rather than work with Muslim community to recapture these symbols for what they truly represent this proposal will only entrench this distorted view that the symbols themselves are representative of some evil or hateful ideology. It is now a long road to travel after this to the point where the religion itself then is seen in this way. - We note that the Explanatory Memorandum in the section quoted above, and at other points in the document, is at pains to highlight the religious nature of the Swastika, the importance it plays in the religious observance of the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religions and why a different name is used for this symbol. No such consideration is given, however, to the very same issue with respect to Islam and Muslims. There is no attempt to recognise the importance of these symbols to Muslims or to distance the symbols themselves from Islamic State. There is an explicit acceptance that these symbols belong to, and represent, Islamic State with only a token attempt to then distinguish the Islamic Faith itself from Islamic State. This approach is ill-considered and fundamentally wrong.

Finally, on this point, there is a fundamental difference between the Swastika, its importance to those named religions, and Islamic State and the symbols we are discussing. The Swastika, as co-opted by the Nazi regime, was never linked by them to any of the religions where it plays a role. So, in the public sphere, the Swastika is not readily identifiable with any of those religions. Education or awareness campaigns may be sufficient to distance the use of the Swastika for religious purposes from those who use it to incite hatred or racism – because it is not inherently associated with the religions themselves. This unfortunately is not the case with the Islamic symbols.

From its inception Islamic State co-opted the Islamic symbols being referred to and in the eyes of a misinformed public those symbols have become indistinguishable from Islamic state, and are linked to the faith itself, such that there is likely to be a presumption formed about any individual who displays them in any way without an allowance or nuance for the circumstances of how this may occur. - Finally, the Explanatory Memorandum concludes that “Accordingly, these measures promote the rights in Article 18 of the ICCPR.” While this may be the case for the other religions referred to, we strongly submit that it is not, and would not be the case, for Islam and Muslims. It is highly likely that the exact opposite will occur, and that Muslims will be restricted in how they are able to manifest and express their faith and beliefs. We do not accept that any benefits in including the Islamic symbols is so great as to counter the very real and tangible disadvantage that may arise for all Muslims.

It is for these, and the other reasons outlined herein, that AFIC opposes the inclusion of Islamic symbols in the proposed Bill.

4. Substantive Submissions – Schedule 2

The Bill also includes Schedule 2 which establishes a new criminal offence for using a carriage service for violent extremist material; and possessing or controlling violent extremist material obtained or accessed using a carriage service. The Explanatory Memorandum states the following in relation to this new crime:

“9…. While it is [currently] a crime to possess material that is connected with a terrorist act (for example, sections 101.4 to 101.6 of the Criminal Code) it is not currently a crime to deal with violent extremist material where, for example, planning or preparation for a terrorist act has not yet begun. This Bill would fill that gap by creating new offences for using a carriage service for violent extremist material (new section 474.45B) and possessing or controlling such material that has been accessed or obtained using a carriage service (new section 474.45C).

10. Examples of the types of violent extremist material intended to be captured by the offence include instructional terrorist material and terrorist organisations’ recruitment materials, which are aimed at disseminating extremist views and promoting violence.”8

The Memorandum goes on to explain the rationale behind this proposal as follows:

“178…. These provisions attach criminality to the circumstances in which material is possessed, however there is currently no Commonwealth offence that attaches criminality to the nature of material possessed or dealt with. These existing offences also require a connection to a terrorist act, which means law enforcement may be unable to intervene at an earlier stage….

181. By attaching criminality to the nature of material possessed, the offences would reflect the harm that is inherent in violent extremist material. Violent extremist material is harmful because it facilitates radicalisation. Violent extremist material may encourage and assist in planning violent acts. These acts can threaten public safety, and Australia’s core values and principles, including human rights, the rule of law, democracy, equal opportunity and freedom. While Australians are free to hold and communicate a variety of beliefs, the use or advocacy of violence to promote these beliefs is unacceptable. Violent extremist material adversely affects social cohesion as it can vilify and portray or encourage violence against certain groups in society. Australians have the right to live free from discrimination, hatred and violence…

188. New paragraph 474.45A(1)(b) would set out the second of the requirements for violent extremist material. It would require that, in addition to the material meeting the requirements in paragraphs 474.45A(1)(a) and (c), a reasonable person would consider that, in all the circumstances, the material is intended to, directly or indirectly, advance a political, religious or ideological cause. “9

While the principal of protecting society and individuals from harm caused by violence and violent extremism is admirable, we are concerned that this proposal tips the balance against civil rights and freedoms more than is warranted in the circumstances.

As is noted there already exists crimes where such material is possessed in preparation for an act of terrorism, what this proposal seems to be doing is to move that culpability even further away from the commission of an actual act of violence. The proposed law would make it a crime for the mere possession of such material, where a carriage service was used to access it, store it or deal with it in some way without any further requirement.

The rationale for this being that it will allow law enforcement to intervene at a much earlier point in the path to what is presumed will eventuate as an act of violence. But insufficient evidence has been provided for why this is necessary or what acts of violence may have been prevented previously in such circumstances.

These provisions may very well capture within their remit people who may come into possession of such material from any number of sources, and for any number of reasons, but who will never and will never have gone on to commit any act of violence. The way the Bill is currently drafted, in practice, the mere possession of such material on a device that is defined as a carriage service will be enough for prosecution to take place.

We have seen the continuing growth of National Security and Ant-Terrorism legislation over the last 20 years, in some cases warranted but in many cases without sufficient justification for the erosion of civil liberties. We are ae concerned that this is another such example.

Further there is no indication of what measures are in place, or would be introduced, to deal with offenders from a rehabilitation perspective, particularly for young people who, in recent history, one would expect to be overly represented in the category of potential offenders. The long-term consequences for the social integration of a young person incarcerated for an offence of such nature is well known and documented. The efficacy of this approach is rightly questioned in matters where no act has taken place let alone what is proposed now where no act is even being contemplated let alone prepared for.

AFIC urges strong caution in pushing the culpability point even further away from an act of violence than it currently is without more robust research and consideration of all the factors involved.

5. Alternative Legislative Options

As previously noted, the current move by the Commonwealth government comes on the back of a rise in far-right activity and the use of Nazi symbols over the last 12-24 months. AFIC supports moves by Government to respond to this trend by banning the Nazi symbols. This can be done without referencing Islamic symbols and giving rise to all the issues we have highlighted above. This has been done in Victoria quite easily.

5.1 The Summary Offences Amendment (Nazi Symbol Prohibition) Act 2022 (VIC)

The above legislation came into effect in Victoria on 29 December 2022 and provides that a person commits a criminal offence if they:

- intentionally display a symbol of Nazi ideology in a public place or in public view, and

- know, or ought to have reasonably known, that the symbol is a symbol of Nazi ideology.

The Victorian Legislation contains similar exemptions and defences as in the proposed Commonwealth Bill but makes no reference to Islamic symbols.

We note that similar legislation exists in NSW – again without reference to Islamic symbols.

5.2 Criminal Code Amendment (Prohibition of Nazi Symbols) Bill 2023

Additionally, we note that the Federal coalition has table a Bill before parliament on this same matter.

A review of the above Bill indicates that it is in a form relatively consistent with what now exists in both Victoria and NSW, albeit it expands the list of Nazi symbols to be banned beyond the Hakenkreuz. Again, there is no reference to any Islamic symbols in this proposed Bill.

AFIC strongly urges the Commonwealth to adopt a Bill that is in similar form to any of the above which will maintain a conformity of legislation across the country and not bring harm or disadvantage to the Muslim community.

6. Conclusion

AFIC supports the overarching principle of banning symbols of hate that are clear and unequivocal and used for no purpose other than promoting hatred, racism or inciting hatred, racism and violence.

AFIC, however, raises serious questions and concerns, as outline above, in relation to the inclusion of Islamic symbols that have been co-opted by the Islamic State. These symbols:

- Are not those of the Islamic State as such and any acts that will give this impression to the general public should be avoided at all costs.

- These symbols are NOT symbols of hatred or racism or an evil ideology.

- These symbols are an important and foundational part of the Islamic faith and are displayed in all manner of ways day-to-day by Muslims.

- There was no call for the banning of such symbols at the height of Islamic States existence. It is questionable as to why there is a need to conflate this with the rise of Nazi symbology at a time when Islamic State is in decline.

AFIC respectfully submits that:

- Islamic symbology would be captured by the wording of s.80.2E as being things that are likely to be confused with, or taken for, the imagery on the Islamic flag and would therefore constitute prohibited symbols. This is an unacceptable position for the Muslim community in Australia to agree to and AFIC rejects this approach in its entirety.

- In effect the outcome of the proposed legislation would be to assign these images, which are central and foundational to all Muslims, to being the sole right of Islamic State and to be associated with their ideology and nothing else – exactly what Islamic State would want. It is for these, and the other reasons outlined in this submission, that AFIC opposes the proposed inclusion of this imagery in the Bill.

- The exemptions and defenses in the proposed Bill are manifestly inadequate to safeguard the rights of Muslims to express their faith as all other Australians would have the right to do.

- AFIC strongly urges the Commonwealth to adopt a Bill that is in similar form to that which currently exists in either NSW or Victoria or which has been proposed by the Coalition. This maintains a conformity of legislation across the country and not bring harm or disadvantage to the Muslim community.

- AFIC urges strong caution in pushing the culpability point even further away from an act of violence than it currently is without more robust research and consideration of all the factors involved.

Yours faithfully

Dr Rateb Jneid President

Religious-Symbols-Submission-July-2023